The History of Bissett – In the Beginning

The following text is excerpted from the book Bissett 100 Years of Gold, by Wilda Ward (2011), with the exception of material in italics. In the early 1900s, all the world was hoping to discover another Klondike Gold Rush. The lust for gold,which never completely died down, was stirred to a fever pitch by tales of the fabulous discoveries in the Klondike. All corners of Canada, however remote, were considered as potential Bonanza Creeks. One such place was the Canadian Shield country lying to the east of Lake Winnipeg. In 1900, the Geological Survey of Canada published a report indicating the area had potential for gold. Prospectors began hunting for the precious metal all across Northern Manitoba, but according to Gold Mines in Manitoba, it was on Rice Lake, near the present day town of Bissett, that the first documented discovery in the province was made.

Two men were the responsible instigators of the gold discovery in this area. These were Ephrem Albert Pelletier, formerly an inspector in the Royal North-West Mounted Police who had travelled widely in northern Manitoba, and Arthur Quesnel, a pioneer entrepreneur who lived and fur-traded in the young community of Manigotagan.

These two men persuaded a number of native trappers to collect rock samples while they travelled through the bush and in the early winter of 1911, one of these, Duncan Twohearts, provided a sample that led to the discovery of gold at Bissett. This event was described in a letter Pelletier wrote many years later, in 1941 :

Duncan Tohart [as Pelletier called him] trapped and traded with Quesnel when I was prospecting in the district in 1910-11. I had met Duncan through Quesnel, and I got him interested in sending us samples of likely looking rock he might encounter on his trap lines. In February 1911 he sent some samples tied up in various pieces of cloth. One in a piece of blue denim looked particularly promising. I crushed it and panned it and it showed colours [that is, traces of gold]. In March of 1911 I took Johnny Wood [of Manigotagan] with me [as a guide], and went to Duncan’s camp at Turtle Lake, where I showed him the piece of cloth. He remembered [where the sample came from] and the next morning we started for Rice Lake. Duncan led me to [what was later known as] the Gabrielle Point, and told me that is where the sample in blue denim came from. A boulder of float rock – rusty quartz – was projecting out of the snow and he had chipped the sample from a corner. We cleared out all the snow we could with snowshoes and shovels and made a big fire with jack pines then growing on the point. The heat of the fire chipped the rock and revealed lots of mineralization and promising looking quartz seamlets. There appeared a seam of oxidation running up the point. So I began picking up this seam, cracking the quartz pebbles as I fished them out, and free yellow gold showed up in one pyrite cavity the size of a small pea. That was good enough for me so I staked the claim [on March 6, 1911 at approximately 3:30 p.m.] and named it Gabrielle. I returned to Winnipeg, registered it and returned the same month with dogs, five loads of provisions and Desautels [whom he had hired as a canoe man and helper]. I prospected until open water and came out in a birch bark canoe Duncan made for us, and that summer, 1911, Gabrielle Gold Mines was incorporated.

The Gabrielle Mine, which Pelletier and Duncan Twohearts discovered in 1911, no longer exists as a separate entity, but it remains a vital part of the on-going mining developments at Bissett. Not only did this find open up the gold scene in the Rice Lake area, it was the first gold find in the province of Manitoba. And all of this happened because of a chance meeting between Pelletier and Oswald Quesnel in 1909.

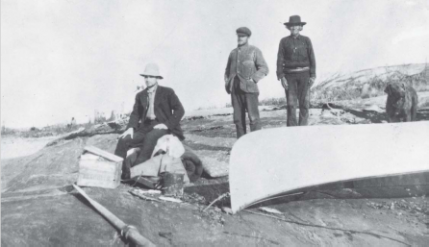

Oswald Quesnel, E.A. Pelletier and Duncan Twohearts

Photo courtesy of W. Ward.

One June 28, 2009, San Gold, the current mining company at Bissett, officially honoured the contribution Duncan Twohearts had made to Bissett and its mines in a ceremony held at the Gabrielle Point, at the site of the first discovery ninety eight years earlier. Sixty of Duncan’s descendants attended the ceremony as well as dignitaries such as Assembly of First Nations Grand Chief Phil Fontaine, Liberal MP Tina Keeper (Churchill), Conservative MLA Gerald Hawranik (Lac du Bonnet), and various San Gold Mine officials, including Executive Chairman Hugh Wynne, whose father Charlie had also been involved in the original development of the Gabrielle Mine.

The staking of the Gabrielle claim by Ephrem Pelletier on March 6, 1911 was the start of what came to be known as The Rice Lake gold rush. However it was only the first claim he staked in the area. Others included the Emma and the Rachel all of which were named for his female relatives. The Gabrielle was named for a favourite cousin, the Rachel for his sister and the Emma for his mother. These claims were all staked along the north shore of Rice Lake, and were only the start of feverish activity in the area. Pelletier got in fast and he got in early, before any other eager prospectors could find out about his initial discovery.

After travelling out to Winnipeg to register the Gabrielle claim as soon as possible after he staked it, Pelletier wasted no time in returning to what he must have regarded as the mother lode. This time he came in fully equipped with dogs because there was still snow on the ground and the rivers were frozen. He also brought in five loads of provisions and a canoe man named Alexandre Desautels whom he hired to help him.

Desautels was not a prospector. He was a French Canadian from St. Boniface. As a child he remembered seeing Louis Riel, and he received his education at St. Boniface College, enrolling in the year of its founding in 1881. However he became known first and foremost as a voyageur and canoe man of the old school…….

Pelletier and Desautels camped on the north shore

of Rice Lake in the spring of 1911…..

On the morning of May 16, Pelletier remarked to Desautels,

“We’re getting short of grub. I think I’ll take a walk along the east shore of the lake and see if I can see

any sign of moose.” So he set off, leaving Desautels back in camp….. As the day wore on and Pelletier didn’t return, Desautels decided to take a break. He got into their canoe and paddled over to the first island lying offshore on the north side of the lake. It was a high, rocky island. He climbed up the rocks and began digging around. Before long he discovered what looked like quartz in the underlying greenstone of the rock. He knocked off a few pieces and took them back to camp. When Pelletier

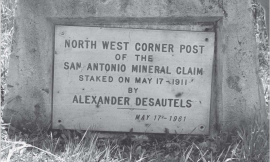

finally returned that evening, Desautels showed him the rock samples and Pelletier… got Desautels to stake it, using the one-line staking which was typical of his day. This discovery line, as it was then known, extended 1500 feet. When the claim was later surveyed, probably around 1919, a north west corner post was erected on a spot which is now marked by a cairn and a plaque, commemorating Desautels’ discovery…..

Once this claim was staked, Pelletier took Desautels with him into Winnipeg to register the claim. Desautels wanted to name it the St. Antoine (or the St. Anthony, according to some versions of this event) after his patron saint. But in Manitoba only one claim can be given a particular name, and the Mining Recorder said there was already a claim by that name. Pelletier said, “Why don’t you make it Spanish then, and call it the San Antonio?” And so it was that the claim was duly recorded as the San Antonio claim.

However Desautels never developed the claim he had staked…..

The two men went into the saloon at the Corona and Pelletier asked Desautels, “What are you going to do with that claim? Work it or sell it?”

Desautels, who wasn’t an experienced prospector and wasn’t really interested in mining said “I’ll sell the

bloody claim to you for ten cents.”

Pelletier very generously gave him a dollar for the claim, which money they then used to buy a round of

drinks to seal the transaction. Desautels was left with a profit of 75 cents on the deal.

You might wonder as I did why Pelletier got Desautels to stake this claim when he so obviously wanted it himself. The answer to this question lies buried deep in the past, in old mining regulations which

state in part:

“#17 Any person having located and recorded a mineral claim under the provisions of these regulations, shall not have the right to locate another claim in the same mining district, either in his own name or in the name of any other person, for his benefit, for a period of 20 days from the date of such location.”

Under this regulation, Pelletier was therefore unable to stake the claim himself, but by getting Desautels to stake and register it in his own name, and then getting Desautels to sell it to him, Pelletier was thus able to legally acquire this claim. He went on to parlay it and others he had staked in the area into what eventually became San Antonio Gold Mines. This San Antonio claim was the claim which proved to be the key, leading to the development of the mine which made millions of dollars for the company, which subsequently bought it from Pelletier in 1926, and was the reason for the birth and growth of the town of Bissett.